Restaurants and bars across the country have closed their doors to limit the spread of COVID-19.

New Orleans to Seattle business owners are dealing with overwhelming indecision and financial threats, while servers, dishwashers, cooks, and bartenders are almost instantly without a job.

The second most common occupation in the USA is food preparation and service. Waiting tables is the eighth most common occupation.

More than 12 million Americans work nationwide at more than 600,000 food service and drinking establishments.

As of 2016, Americans spent over half of their food budget eating outside their homes.

Fuelled by this growing trend, bars and restaurants have played an important role in recovering the country from the Great Recession.

Between 2009 and 2018, the number of establishments increased by 17 percent, accounting for over 75 percent of all growth in the leisure and hospitality sector during this time.

Such “third places” are the lifeblood of many American towns, which are crucial to our cultural fabric and base of employment.

This article captures how COVID19 affected the restaurant industry and will provide some stats behind how COVID19 affected the restaurant industry.

How COVID19 Affected The Restaurant Industry? Early Stages

The pandemic’s initial impact was a sudden drop in customers. That has a huge effect on both the income of a server and that of the owner.

Several business owners and managers confirm that there was insufficient customer response to delivery and take-out orders.

“We decided to do [take-out and delivery] at first, and we had zero foot traffic,” says a restaurant and entertainment center manager in Virginia.

‘’We are right in the center of town. This is where you can see apartment buildings.

We provided delivery at the apartments and said we would bring them food to try and remain open.

We only were able to sell $300. Labor costs were roughly $600.

Unfortunately, because of this, we thought we had to lock our doors.’’

For many business owners, the next step was to consider how long they could keep their workers on payroll, and how to communicate with them about shutting down.

‘’I committed to keeping the team together with our employees, because we have a management team and marketing guy, and sales,’’ one owner explains.

‘’We have a very tight team of people, but everyone has to take a pay cut of 20 percent. I am the owner and take no pay.

I’m trying to leverage or sell some business equity to help raise money to cover those people so they don’t end up unemployed.’’

Not every owner is as protective of their employees.

One bartender mentioned that she did not receive official correspondence from management about not returning to work until several days after the establishment was closed.

‘’I had a shift onMarch 14 that was canceled and they never said anything to me’’, says the bartender. “Being an employee, I do not feel valued. I doubt any of us does.’’

A Baltimore brewery owner, reflecting on what is happening across the sector, shared his concerns that small restaurants will have even more difficulty maintaining payrolls, which he believes will have an almost immediate impact on workers.

‘’Small businesses in this country make up a huge proportion of jobs, and when you hit pause for the hospitality industry and a lot of small manufacturers, the payroll is just the first thing to suffer,’’ says the owner of the brewery.

‘’Even a really successful restaurant can have a margin of 10 percent, and if you have a big payroll every week and that’s your biggest expense, that doesn’t go very far.’’

Even after the lights are switched off and the staff is laid off, restaurants and bars are still owing rent.

For one owner of a small, family-run mall food stand, that was the main issue.

‘’We are really scared of how the rent is going to be paid,’’ she told us.

‘’The rent is super expensive, and we are not making any income.’’

A manager at a restaurant in Virginia said, ‘’One of the things Italy has done is rent forgiveness … if they were to execute rent forgiveness for the month, it would benefit small businesses all over.

My restaurant rent is $25,000 a month. We even ended up making $150,000 in sales in our slow month, last month.

What happens when that drops down to less than $10,000 and we have to pay $25,000 in rent and our loans?”

In addition to rent and debt, some operating costs, and other sunk costs such as insurance premiums is not as easy to turn off as the utilities are.

Small businesses need extra liquidity — quickly — to fulfill these obligations, or they will have no choice but to fail.

The federal government has been moving relatively rapidly with the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the CARES Act to provide some support for small businesses and unemployed workers.

The latter provides businesses with under 500 workers affected by the coronavirus with $350 billion in loans, including up to eight weeks of compensation for those salaries, insurance, and other qualifying expenses.

But it is unclear whether that package will be sufficient or not.

What is Happening to Workers?

A traditional food and beverage establishment hires front-of-house workers (such as servers, bartenders, hosts, and bussers), back-of-house workers (cooks, dishwashers, and food preparers), and managers or supervisory personnel.

Work arrangements in this sector range enormously from entry-level, mostly part-time employees with no health insurance or other benefits (more common in smaller or lower-cost establishments) to highly experienced, full-time employees with benefits (more common in high-end and larger firms).

According to a study by Brookings, workers, managers, and owners alike mentioned feeling overwhelmed and terrified by what would happen to the industry in the months ahead.

They interviewed servers and managers in different financial positions depending on whether they had savings, debt, health conditions, or a partner who was employed or had health insurance.

Several have noted that most of the industry’s workers tend to live paycheck to paycheck.

The top concerns of the workers were how to pay their rent or mortgage, whether they would lose their health insurance (if they had it), what they would do if they got sick (especially if they didn’t have health insurance), how they would pay for food and utilities, and how they would get deeper into debt than they already were.

Some of the workers and managers interviewed had health insurance through a partner but most said that by the end of summer they were uninsured or would lose their health insurance.

The CARES Act does not provide provisions for those who are or may become uninsured because of work loss or benefit cuts. Those working in the restaurant industry who contract COVID19 or experience another adverse health event may face heightened medical debt in the months to come, above all else.

Workers and managers interviewed were especially worried about dishwashers at their establishments. Typically, dishwasher positions are very low-paid hourly jobs, often occupied by recent immigrants — both the undocumented and those who have legal work permits.

While the CARES Act extends the eligibility of unemployment insurance (UI) to low-wage workers who would not normally meet the minimum income requirements of their state; however, it does not expand to undocumented workers.

Almost everyone participated in the interview, thought that the federal government’s $1,200 direct payment was a decent start, but would not be enough if the pandemic lasts for several months. Several people interviewed suggested that rent payments to be suspended until the pandemic ends and that landlords can be compensated by banks.

The Stats Behind How Covid19 Affected The Restaurant Industry

As the novel coronavirus has spread all over the world, collateral damage has been widespread while the restaurant industry is suffering one of its heaviest blows ever. While on-the-ground reporting reveals that fact one story at a time, reservation apps, point-of-sale systems, and other tech platforms have effectively captured a huge snapshot of the tectonic disruption in their databases— creating a quantifiable picture of just how much the novel coronavirus has distorted American food culture over the last three months.

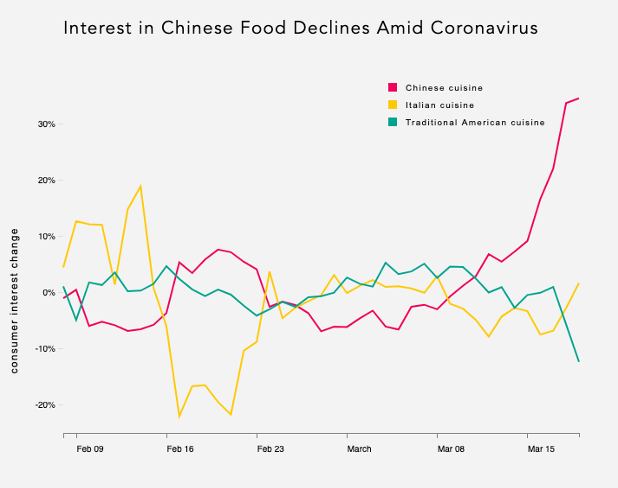

January to February: Americans vs Chinese food

Scientists confirm that the first outbreak of COVID19 occurred in Wuhan, China. This became the epicenter of the soon-to-be pandemic throughout January and February. As awareness of the novel coronavirus and its likely origin grew throughout January, some Americans stopped dining in Chinese restaurants in a xenophobic reaction to the outbreak, leading many across the country to report steep declines in business; some have closed since.

There’s typically an uptick in Yelp searches for Chinese restaurants around the Lunar New Year. In 2019, Yelp searches showed a 56 percent boost on the first day of the Lunar New Year compared to the two weeks before. However, there was only a 38 percent increase this year, while there was an actual decline in Chicago and Manhattan. Then, Chinese restaurants’ share of regular restaurant “connections”—things like phone calls, website clicks, delivery orders, and reviews—went down about 20 percent in the first three weeks of February.

Source: Yelp

In Yelp reviews for businesses in Chinatowns the word “coronavirus” was mentioned at least 10 times more than it was in reviews for businesses in other neighborhoods — many of them were in comments from people urging others to patronize their local Chinatown, a feeling replicated throughout the country. Politicians and celebrities also took to social media to persuade people to visit their local Chinatowns, but throughout February data show continuing declines in the business.

Ironically, what seems to have restored the appetite for Chinese food was the wave of social distance that began to move across the country as people began to avoid large gatherings and became dependent on takeout and deliveries: Interest in Chinese cuisine skyrocketed while interest in other less-takeout-friendly cuisines such as traditional American, Japanese, and Italian sank.

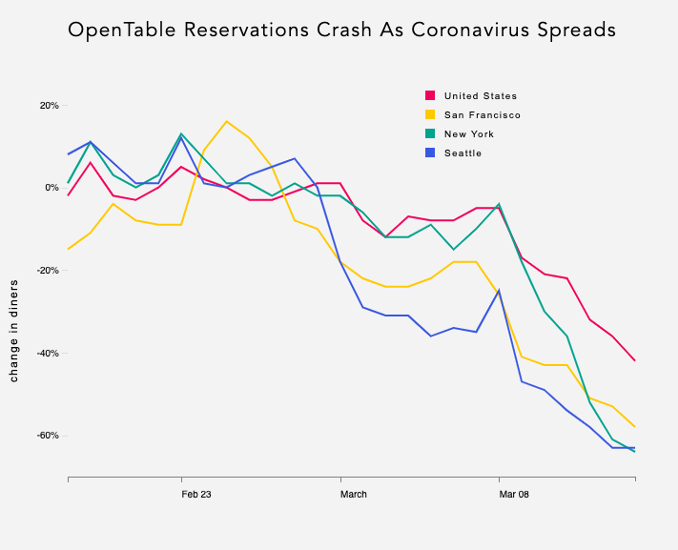

February Into Early March: Dinner Plans Are Canceled

As March approached, several cities along the West Coast such as San Francisco and Seattle saw a growing number of COVID19 cases and deaths.

According to location technology company Foursquare, visits to casual dining restaurants tracked by the service began to decline, falling by around February 24, from 8 to 12 percent.

Not surprisingly, full-service restaurant reservations have seen a fall.

Reservations in Seattle were down 31 percent by March 3 compared to the previous year, according to the OpenTable reservation app.

San Francisco saw a drop of 24 percent. Reservations continued to plummet in the following week, when Seattle and the city of the Bay Area saw a decline of 49 percent and 43 percent, respectively.

Each city with 50 or more restaurants using OpenTable at that stage saw reservation declines as people were staying increasingly at home.

By March 8, multiple states had declared a state of emergency, including Washington, California, and Florida — where some of the first novel coronavirus deaths occurred.

Since some people were likely leaning towards drive-thru or pick-up options, the company found that visits to fast-food restaurants actually increased between 19 February and 13 March week.

Source: OpenTable

Resy, a reservations booking platform, sent an email to restaurant customers on March 11 warning them to ‘’anticipate significant declines in coverage and revenue in April and May.’’

The email explained that Seattle reservations were a third lower than normal at the beginning of the month.

Cancelations in the city have soared past 13 percent, close to rates seen in 2019 during the record-breaking blizzards in Seattle.

Cancelations in New York City were 45 percent higher than last year in March.

‘’Restaurants should urgently consider excessive overbooking to counter the expected increase in cancellations and drop in walk-ins,’’ the email said, days before cities across the country will start closing down dining rooms at restaurants.

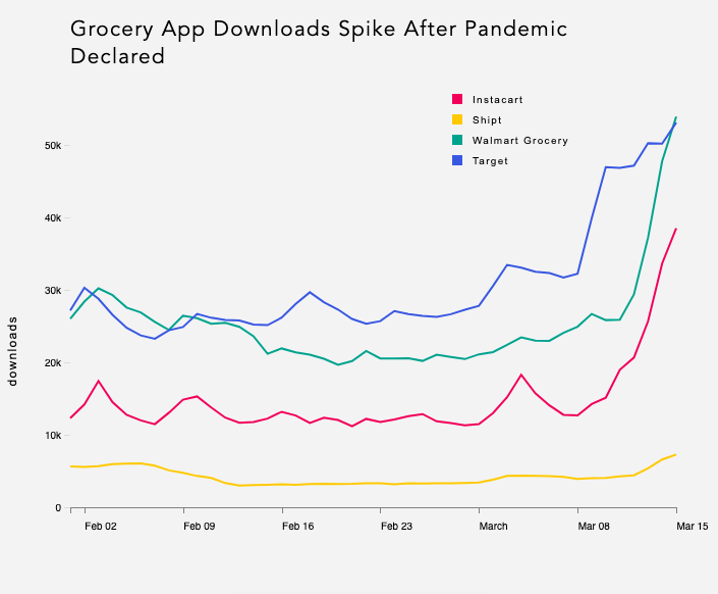

Early March: Americans Choose Grocery

The World Health Organization officially classified COVID19 as a pandemic in the second week of March, and the United States borders were closed to most European countries.

When calls for people to isolate themselves and exercise “social distancing” were all over the screens, many Americans avoided going to restaurants entirely and prepared to stay home and cook for themselves.

Apptopia, an analytics company that monitors regular downloads of mobile applications, reported huge increases in downloads for grocery delivery devices that week.

Downloads for Instacart grocery delivery app increased 215 percent from 14 February to 15 March. Apptopia data shows, Instacart downloads spiked 50 percent over the weekend following the designation of coronavirus as a pandemic, while downloads for Walmart’s grocery app grew 45 percent. (The big-box brand recently announced that the stand-alone grocery app would be slowly withdrawn and merged with its general app.)

Source: Apptopia

When cities prepared to enforce social isolation, residents poured into stockpiling grocery stores. Visits to bulk-buying grocery stores such as Sam’s Club and Costco increased almost 39 percent in New York City, Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles from February 19 to March 13 week, Foursquare data shows.

From March 8 to March 18, Yelp also saw a 160 percent rise attention to grocery stores over dine-in facilities, among other increases in interest for produce and takeout.

Faced with cooking for an extended period of time, people have turned to technology to find out how to prolong the shelf life of all the food they purchased.

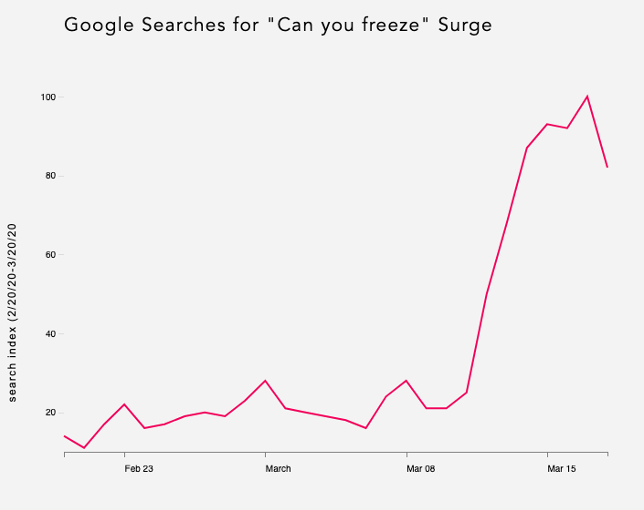

Google Trends reveals that searches for ‘Can you freeze’ exploded after March 12, with ‘Can you freeze tofu’, ‘Can you freeze half and half’, and ‘Can you freeze tortillas’ broke out in searches in the category of food and drink.

Source: Google Trends

Mid-March: Restaurants Were Closed

With the number of COVID19 cases in the United States reaching 2,000 by mid-March, many state and city officials announced executive orders to shut down all on-site dining restaurants and bars.

During that time, Yelp saw a considerable shift in interest from dine-in to delivery and takeout options. By March 18, overall daily restaurant connections were down 54 percent; pizzerias, however, were up by 44 percent.

The forced closure of dining rooms means restaurant businesses and their staff will be taking a tough hit in the coming months. However, the effects can be seen immediately: Temporary workers lost hours or were laid off altogether, as many restaurants were closed.

According to Homebase, a free scheduling and time tracking tool for small businesses, by March 17 the total number of hours worked for local businesses in the food and drink sector had dropped by 40%, while overall the number of hourly workers decreased by 45%.

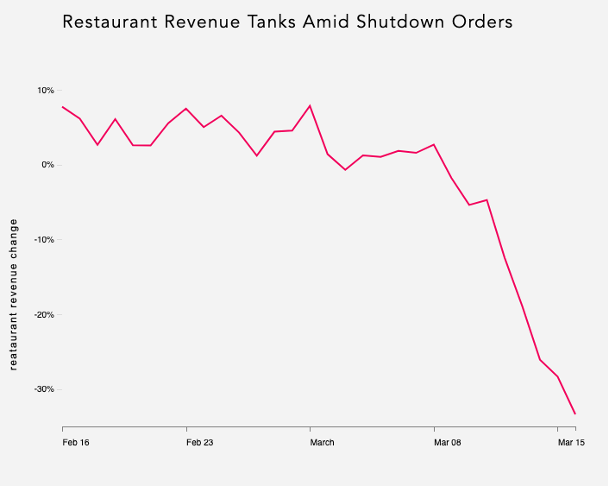

Revenue statistics from customer service software company Womply, which records sales from 48,000 restaurants, indicates slightly lower revenue from restaurants than the estimates from last year.

The day that Mayor Bill De Blasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a reduction in capacity for restaurants in New York City as early as March 15, revenue was already down 25 percent.

Source: Womply

It still remains to be seen how COVID19 affected the restaurant industry.

To truly survive the crisis, something drastic will have to be done for the restaurant industry — particularly small, non-chain restaurants.

A variety of fundraising campaigns and non-profit grassroots initiatives may alleviate or delay some of the losses suffered by restaurant owners and employees, but short of a massive, government-sponsored bailout in the form of rent reductions, tax deferment, disaster relief loans, and other forms of relief, it is hard to tell what the restaurant industry will look like when we eventually leave our homes in the coming weeks or months.